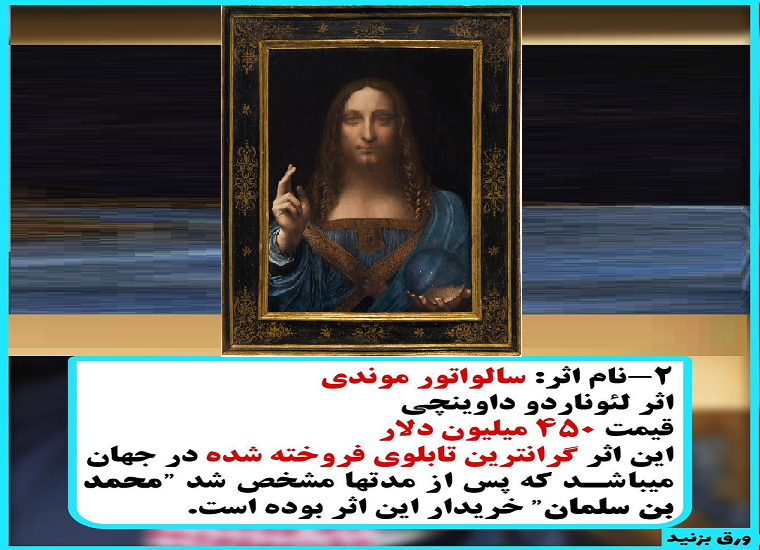

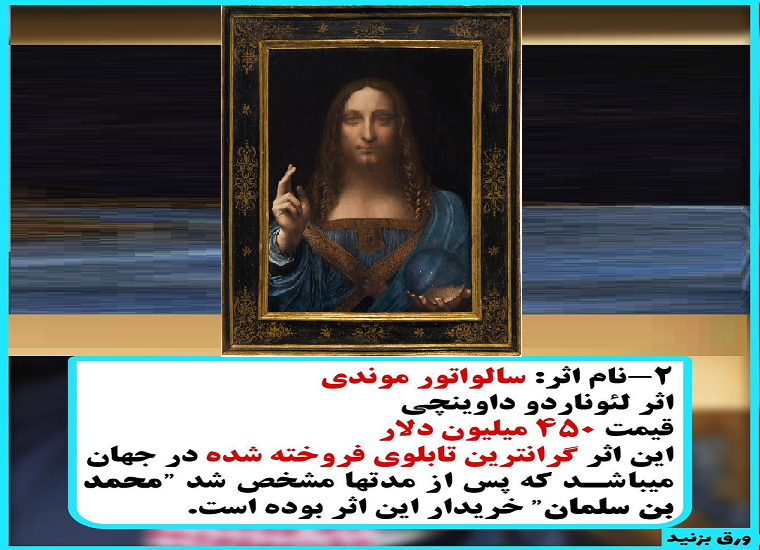

In May 2008, some of the world’s greatest Leonardo da Vinci experts stood around an easel in a skylit studio high above Trafalgar Square. The object they had been invited to scrutinise, in the conservation department of the National Gallery, was a painting on a panel of walnut wood. It showed a long-haired, bearded man gazing straight ahead with one hand raised in blessing, the other holding a transparent sphere.“There’s a mixture of being excited but not getting caught up in it,” says Martin Kemp, the eminent art historian who was there that Monday. “I try to keep a gravitational pull going, saying, ‘This can’t be right.’” Yet the thrill in the room was tangible. The painting had “presence”, felt Kemp, and there was no dissent. That day, a long-forgotten old picture was authenticated as Leonardo’s lost masterpiece, Salvator Mundi (Latin for Saviour of the World). Three years later, in November 2011, this portrait of Christ was unveiled for the first time in the National Gallery’s blockbuster Leonardo exhibition. Six years after that, it became the most expensive painting ever auctioned, when it sold at Christie’s for the stupendous sum of $450.3m (£342.1m).

In May 2008, some of the world’s greatest Leonardo da Vinci experts stood around an easel in a skylit studio high above Trafalgar Square. The object they had been invited to scrutinise, in the conservation department of the National Gallery, was a painting on a panel of walnut wood. It showed a long-haired, bearded man gazing straight ahead with one hand raised in blessing, the other holding a transparent sphere.“There’s a mixture of being excited but not getting caught up in it,” says Martin Kemp, the eminent art historian who was there that Monday. “I try to keep a gravitational pull going, saying, ‘This can’t be right.’” Yet the thrill in the room was tangible. The painting had “presence”, felt Kemp, and there was no dissent. That day, a long-forgotten old picture was authenticated as Leonardo’s lost masterpiece, Salvator Mundi (Latin for Saviour of the World). Three years later, in November 2011, this portrait of Christ was unveiled for the first time in the National Gallery’s blockbuster Leonardo exhibition. Six years after that, it became the most expensive painting ever auctioned, when it sold at Christie’s for the stupendous sum of $450.3m (£342.1m).

The Most Expensive Paintings In The World

In May 2008, some of the world’s greatest Leonardo da Vinci experts stood around an easel in a skylit studio high above Trafalgar Square. The object they had been invited to scrutinise, in the conservation department of the National Gallery, was a painting on a panel of walnut wood. It showed a long-haired, bearded man gazing straight ahead with one hand raised in blessing, the other holding a transparent sphere.“There’s a mixture of being excited but not getting caught up in it,” says Martin Kemp, the eminent art historian who was there that Monday. “I try to keep a gravitational pull going, saying, ‘This can’t be right.’” Yet the thrill in the room was tangible. The painting had “presence”, felt Kemp, and there was no dissent. That day, a long-forgotten old picture was authenticated as Leonardo’s lost masterpiece, Salvator Mundi (Latin for Saviour of the World). Three years later, in November 2011, this portrait of Christ was unveiled for the first time in the National Gallery’s blockbuster Leonardo exhibition. Six years after that, it became the most expensive painting ever auctioned, when it sold at Christie’s for the stupendous sum of $450.3m (£342.1m).

In May 2008, some of the world’s greatest Leonardo da Vinci experts stood around an easel in a skylit studio high above Trafalgar Square. The object they had been invited to scrutinise, in the conservation department of the National Gallery, was a painting on a panel of walnut wood. It showed a long-haired, bearded man gazing straight ahead with one hand raised in blessing, the other holding a transparent sphere.“There’s a mixture of being excited but not getting caught up in it,” says Martin Kemp, the eminent art historian who was there that Monday. “I try to keep a gravitational pull going, saying, ‘This can’t be right.’” Yet the thrill in the room was tangible. The painting had “presence”, felt Kemp, and there was no dissent. That day, a long-forgotten old picture was authenticated as Leonardo’s lost masterpiece, Salvator Mundi (Latin for Saviour of the World). Three years later, in November 2011, this portrait of Christ was unveiled for the first time in the National Gallery’s blockbuster Leonardo exhibition. Six years after that, it became the most expensive painting ever auctioned, when it sold at Christie’s for the stupendous sum of $450.3m (£342.1m).

newsoholic Time to become News Oholic!

newsoholic Time to become News Oholic!